An overview about data sharing on microservices

Jun 20 2021

Table Of Contents

- Event log

- Event log vs Messages broker

- Event driven architecture and domain driven design

- Events driven architecture side effects

This post is an attempt to expose some concepts about microservices and data sharing that I have been learning recently. The main aim is to keep them as a summary but not to go deep into the details.

Sharing data is a key concept in microservices

Microservices are designed for independence and autonomy. This involves each service being able to be developed and deployed separately, with the idea of parallelizing each stage as much as possible.

Each service is in charge of some business functionalities. These responsibilities define the scope and the data that will be required to fulfil them. Based on this scope, each service will be the owner of a part of the whole data ecosystem.

To provide as much independence as possible, each microservice should have its own data storage, which usually means having a different database. But microservices are not data silos, they need to share information to complete those functionalities. This is why the approach of how to share data is so important.

Sharing data: Synchronous requests

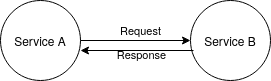

Since all microservices will need to share information at some point, we need to think about the best approach. The simplest one is using synchronous request between services, so whenever a service need information that is stored in other systems, it must be able to fetch it using, for example, an API REST.

It sounds simple, but there some concerns to take into account:

1 - What happens if the system that should answer the synchronous request is down? This is a dependency between services since the client service won't be able to continue until his request is answered. This is a red flag for microservices design since it violates the independence principle.

2 - Let's imagine a service client that needs to fetch several times for the same data. We may think that we are overloading the service with the information, so it may make sense to use some kind of cache to be able to load the information without having to call the other system so many times. The main problem with this kind of cache approach is that we don't know if the data in the cache is in the latest version. This is commonly known as stale data.

3 - Another consideration is the scalability of the approach. The more services we have in the system, the more crossed request will be done among services. So we should think that this approach will penalize our environment in the long term.

The level of resilience of each microservice is determined by its level of autonomy, which is drastically reduced if it has to ask for any information from other services at any time.

Sharing data: Event driven approach

What if instead of having to ask other microservice, the client service already had stored the required information in his database?

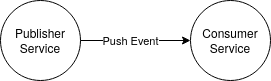

At this approach, each service publishes a message whenever something is modified in its data context. The interested consumers receive these updates as soon as they happen, storing the useful information in their database. Now the service can fetch the information from his data storage, instead of having to synchronously ask other services, removing any temporal coupling.

Normally those messages are known as events. We can reason about an event as an immutable record that is self-contained and that represents an action that has been done at some point in the past.

We can summarize this approach as:

1 - In a microservices environment, each service is the owner of a limited part of the data, this defines the context of each service.

2 - Each data owner will publish an event/message whenever a create/update/delete happens in any of the entities/objects that are part of his context.

3 - The event is published to an event log system, like kafka. This system will be in charge of guaranteeing that the message is consumed at least once in each interested microservice.

4 - The services interested in the event process the change, applying any required modification in his data context.

5 - Normally, not all the published information is required by the consumers, so they process it and build some new objects/entities part of the consumer context with just the information required by them.

Event log

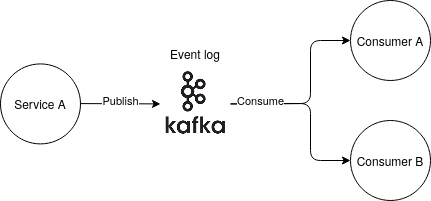

It is possible to directly send messages from one service to another but normally an event log is used as an intermediate system. The event log is in charge of listening to the events from the producers and push the messages to the interested consumers. The main benefits are:

1 - Logical decoupling. Adding more consumers is transparent to the producers since they don't know about consumers, they just know about the event log where they have to publish the events.

2 - Temporal decoupling. Consumers and producers are asynchronous since producers just need to publish to the event log, they don't care about when the messages will be consumed.

3 - At least once delivery guarantees. The event log ensures that each message is processed by the interested consumers at least once. Since a client can crash at any time, the event log usually implements an acknowledge mechanism that is followed by the consumers, they have to explicitly acknowledge to the event log when the processing of an event has finished.

In the case of a consumer that has finished consuming an event, but that falls just before sending the ack to the event log, the event will be resent to the consumer just after it is up again. This can provoke one event to be consumed more than once. The capacity of applying the same action several times generating always the same effect as is only one were applied is known as idempotency.

Idempotency is a critical feature in cloud native applications since there are lots of network communications among services, and, usually, a service cannot ack an action but it has already effectively applied it.

Event log vs Messages broker

Kafka is the most known event log, it allows broadcasting events to various consumers, it persists the events sometime after being delivered to the interested consumers and it allows new consumers to replay the old stored events.

There are other possible approaches like using a messages broker. RabbitMQ is an example of a messages broker, where the main difference is that it doesn't persist any event after the message is delivered to the consumer.

The main advantage of having persistence of the events after being consumed is that it enables to replay past events, allowing to replicate any state in time of any service. This is an ideal case since we have to take into account that the capacity to store events in an event log is not infinite, so at some point, it must start deleting old events.

Event driven architecture and domain driven design

The technique called Event Sourcing, part of domain-driven design (DDD), applies this idea of communicating services using events. Similarly, it involves saving all the events in a events log/store where the rest of the services can consume them.

Each event is an immutable fact already validated by the producer, this means the rest of the services are forced to consume it to avoid desynchronization.

In DDD, the scope of each service is known as the bounded context that matches the idea of each service being the owner of a part of the data domain.

Events driven architecture side effects

At first sight, the use of events to share data around different services looks like an ideal approach since it fits good with a microservice architecture since it provides scalability, temporal decoupling and independence. However, we should take into account some complex about it:

1. State initialization and recovery. When setting up a new service, we need to provide a way to initialize his data context.

Ideally, it would be possible to regenerate the derived data from the event log. In case of needing data that is not in the event log (maybe because the event log data has a TimeToLive configuration), the producer system must provide a way to send this information to the consumer.

An important detail is that any consumer service is resilient to temporal downtimes since the events are persisted in the event store until they are consumed.

2 - Replication lag and eventual consistency. One downside is that events consumer are asynchronous, so there is a possibility that a user may read from a service that doesn't have the latest version of the data, the client will read a stale version of the information.

This idea is related to the consistency requirements of a system. Although some services may be in a stale status for some time, in the end, the system will converge to consistency, which is known as eventual consistency.

This concept is similar to replication lag, which is used in distributed databases when a replica is out of date because still has not received the last update from the master database.

3 - Events ordering. To have a consistent system we need to pay attention to the order in which the events are consumed by the client. Consuming an unordered event may lead to an inconsistent status.

When possible, the simplest approach is to funnel all the events through one publisher and read them only from one consumer. This way we force all the events to be processed sequentially in the same order as they were published.

At some point, we may need to scale this approach since a single node could not fulfil the throughput requirements. In this case, we could start using different partitions to route the events.

Delivery order inside the same partition is guaranteed but not across them. It is required to send events to the same one to keep the casualty relations between them.

References

- Designing Data-Intensive Applications, by Martin Kleppmann